Botswana and the KhoiSan: Connecting Ancient Traditions with Modern Life

This is the final post of a 4-part series on our experience in the remote Kalahari Desert of Botswana with the “Bushmen” or KhoiSan people from the Ju!Hoansi Tribe back in April 2019. See our Instagram Story Highlights Botswana here for quick videos, though a longer video will be created in the next several weeks and shown on our YouTube Channel (please subscribe here). Our website is the best place to sign-up for email updates of new posts! Thank you for sharing in this adventure.

—-

Cover Photo: The morning after a heavy rain brought to the Kalahari by the KhoiSan trance dance the night before.

Our time with the KhoiSan, as I’ve already described, was nothing short of enlightening, but on two of our three nights, the trance dancing made it magical. The power of these experiences was the collective symphony of several elements that by themselves are rooted in powerfully ancient wisdom.

The Elements

Circles themselves have long been symbolic in ancient cultures as a means to meditate, heal, and gain power. Whether one is drawing one (like Japanese calligraphy) or forming one through body formations (sitting or dancing), they require concentration to perfect. One indigenous elder from North America, Black Elk, in his book, Black Elk Speaks (1961), rightfully instructed:

Everything the Power of the World does is done in a circle. The sky is round, and I have heard that the earth is round like a ball, and so are all the stars. The wind, in its greatest power whirls. Birds make their nest in circles, for theirs is the same religion as ours. The sun comes forth and goes down again in a circle. The moon does the same and both are round. Even the seasons form a great circle in their changing, and always come back again to where they were. The life of a man is a circle from childhood to childhood, and so it is in everything where power moves.

As a youth practitioner and trainer in the earlier part of my career, I played with the energy of circles a lot. I learned (and would teach others) how to create intimate spaces where the energy exchanged, and shared by those co-creating the space, could be guided to elevate and intensify to achieve whatever experience the collective whole was trying to achieve. My comfort zone for using this energy has always been in the space of healing and creation; and my struggle has always been patience with unstructured playfulness.

The element that distinguishes the evolution of humankind is fire. In its raw form, an element that serves as a catalyst for protection from the cold, enemies, darkness, and even illness (through cooking). At its best, a source of purification and at its worst, the power of death and destruction, fire itself is mesmerizing and hypnotic. This natural element has been revered and symbolized by every major culture and tradition in the world; its imagery used for invoking the Divine and for foreboding of the fires of the afterlife. Whatever one’s association is with fire, its power cannot be denied or taken for granted. For me, there is great comfort in lighting candles and wonder in watching the its flame flicker and dance.

Finally, the energy of rhythmic sound is perhaps the greatest multiplier of energetic exchange. Percussion is innately familiar as our mother’s heartbeat is the first sound we hear in utero, and our own is the one we hope we continue to hear. Sound creates vibrations that are felt in the body and can jolt someone into a focus when they were otherwise distracted. Whether in a drum circle, or with a choir, I have always felt a presence around live energetic sound and even more so when I am participating in its creation.

The night trance dancing with the KhoiSan combined all of the elements mentioned above to create a powerful energetic experience for those lucky enough to observe it, and even more so for those who chose to be a part of the circle.

Trance Dances and Healing

When we arrived to their camp after dinner, the KhoiSan were already in the full swing of their dance ritual. The women were sitting shoulder to shoulder, clapping and signing songs in varied parts, around a strong fire. The men were stomping in a circle around them, wearing rattling chains made from seeds. Some of the smaller children and babies were asleep in the skins tied on their mothers; the older kids were hanging around a smaller fire in the back of the area. The night was clear and star-studded and it felt as if the all of the life in the Kalahari desert was quietly listening to the enchanting melodies from the KhoiSan.

We were told we could observe or participate, as we wished. Both because we were with the kids who seemed a tiny bit nervous about the new experience, and because we didn’t want to presumptuously impose, we sat just outside the circle and tapped our feet to the beat. The heat emitted from the fire seemed to propel the energy of the group and the rising smoke seemed to carry the musical voices high above the Kalahari. It was a sight for the senses, an unforgettable moment in time to be forever encased in our collective experiential family memories.

We learned that the dancers were drawing-in spiritual energy from the singing and clapping of the women and as they “felt” that energy, they would begin to enter into an altered state of mind. Thus, the women didn’t pause for long between songs, so as to uphold the momentum. In fact, when the women’s voices seemed to lack the requisite energy for the dancers, one of the old boys, Kgao Qamwould enter the space between the women and the fire and vocally prod them to elevate their voices and vigorous clapping. Conversely, if the women observed someone going into trance, they would naturally increase their volume to ensure that the person in trance was appropriately enveloped in their energetic care.

The old boys were known for their ability to enter the varied level of trance states with skill and relative ease, compared to others. The first night, we watched as Kgao Qam began to stagger with his walking stick and begin to move with a blank expression on his face. As he moved deeper into the state, he was physically guided by one of the others. When someone was fully in the state of trance, he would often touch the “N’num” (the solar plexus, or spiritual center above the belly button; in Eastern traditions called the Jing energy center for Qi/Chi or the third chakra) to invoke a trance in another. Now both in a trance, they would dance together, with the person who was newly in a trance leaning on the back of the other (like a hug from behind).

That first night both the old boys, Kgao Qam and Kgamxoo Tixhao, entered into the second of three trance states, in which they could heal others. We received healings from both of them. Each time, one of the healers would place their hands on our heads or shoulders and chant healing blessings. Kgamxoo Tixhao’s always ended with a shrill shriek at the end before they moved onto the next person in the circle. Since their exertion of energy was so clearly visible, I somehow expected the healing hands to be hot. Instead, they were cold and clammy, yet a clear conduit for some type of energy flow. Each of us separately experienced a rush of energy entering our bodies when they placed their hands on us.

Our Experience

That first night’s taste of trance dancing was enough to dispel the anxiety of the kids. I could tell that they had been a bit nervous about their initial impressions and the intensity of their angst climaxed when observing Kgao Qam reach the first state of trance where he was strongly attracted to the fire, so much so that the others had to hold him back. It was quite a spectacle to see Kgao Qam, an old skinny man who is likely in his late 80s/early 90s being held back, by two strong young men, to prevent his body from flailing itself into the fire. And the KhoiSan who love to tease each other, themselves were amused by the Kgao Qam’s behavior and laughed every time he made his way to the fire.

I should note here, that my above description of Kgao Qam’s appearance, is greatly misleading with respect to the strength and tolerance for discomfort, or even pain, among the KhoiSan. In Kgao Qam’s case, not only did he stomp and sing/shout with enthusiasm for hours (a cardio workout in and of itself) as he floated through the three levels of trance on both nights, but he conducted over 60 healings each night and heated himself up by eating numerous pieces of hot burning coal! More generally, amidst our conversations over the three days, we heard hunting legends of community members who had literally fought for their lives against a leopard (with a terribly scarred body and a leopard carcass to prove it) and a hungry lion. We saw first-hand how fit they were to cover miles of terrain with modest nourishment, laboriously pseudo-hunt for small game (see previous post about Porcupine Hunt), and all of this after pulling marathon-like all-nighters complete with exchange of spiritual energy and visitations with ancestors.

In between the first and second trance dance nights, we began to feel closer to the KhoiSan and were building relationships with many in the group. Two women who I especially befriended on the Bush Walks were K’aru and Shaedxae (pronounced Sid K’ai). Through the joint language of caring for children, we bonded. One might wonder, what do friendships without language look like? Non-verbal friendship manifests in physical expressions of care and generosity—it looks like holding a thorny branch away from your friend’s face as you walk through the Bush, patching a cut up with a leaf, playing games and drawing, helping to carry foraged bounty; making an effort to participate in whatever activity one can, sitting next to each other in circles, and smiling with your whole face. There may be way more gestures and eye contact as both sides seek to understand, or teach things, like ages of kids, uses of plants, etc., but ultimately, its trust—trust that the other sees you with respect and a genuine heart.

So, with this growing fondness for the KhoiSan and increased comfort, we were much more prepared as a family for the second night of trance dancing, though also more exhausted from the Bush Walks of the day. The kids were no longer nervous, but sleepy, and easily fell asleep in our laps and on the ground, amidst the loud melodies of the night. Unencumbered by a sleeping child, I was free to participate in the activities that night.

I saw one of the women join the men in dancing for a few rounds and that was my cue that it was ok to mix the genders in the dancing. I stood up and stomped around the fire a few times. It was liberating and communal…and I felt the same elation I feel when I dance in the community circles at Native American Powwows back at home. After dancing a few rounds, I sat down next to K’aru and joined in the singing. I followed K’aru’s lead and sang/clapped to her part. There I truly felt the energy from the group and appreciated Shaedxae’s leadership more than before.

At this vantage point, two things surprised me, that I hadn’t realized in my previous observational experience. The first was how hot the fire was. The women sat around the fire for hours and when it began to weaken, they stoked it and added more wood. I didn’t realize how hot it was to stay so close, and frankly, I couldn’t do it for more than about 15 minutes. At one point, Kaysee came to sleep in my lap there, but it was too hot for him and the smoke irritated him, even while he was asleep. The second discovery was the amount of energy it took to zealously sing and clap. Aside from staying in the same seated positions for hours which took some level of tolerance, the women were putting their whole selves into clapping and singing in a way that I deeply appreciated after having done it for a few minutes! They were stronger than one might realize and by sitting next to them inside of the dance circle, I understood the truth about how their energy controlled the condition by which the dancers could access their stages of trance. It was beautiful and perhaps, even more impactful on my soul than the dancing itself. K’aru was proud of my catching on and told the other women that I was singing her part. They all smiled at me and for that moment, I truly felt privileged to be included in their circle.

When it was just too hot for me to continue singing, I stood up on my legs that had fallen into a deep sleep and walked over to the kids’ fire. I’ve spent most of my adult life working with kids, particularly teenagers and it is a comfortable zone for me. Professionally, I have learned that one of the best ways to build trust with kids, is through the power of non-intrusive and safe touch and personally, the structure of games creates a comfortable container for me to connect. With the help of Kavaa’s translation on a few occasions, I taught them the “hand-slap game” which relies on quick reflexes and very little talking, some “patty cake” partner hand sequences, and later, the untangling of the “human knot.” They loved these games and I promised that we would play them again in the morning when Zayan, Kenza, and Kaysee were awake.

At this point Kgao Qam and Kgamxoo Tixhao were out on the ground and into the deepest level of trace. They were off in the mountains somewhere, perhaps having taken the form of a leopard which they did years ago. We would have to wait until morning to hear of their adventure. Kapil and I decided to take the kids back to camp, but not before looking at each other and whispering in awe, “where are we right now?” and taking in the moment.

I felt something there. We all did in different ways. Whatever it was….that energy…it has been with me and my mom at Powwows, it was around me in college when I was performing as part of the Gospel Choir, it was there when my mom and I went to the Church of the Latter Day Saints, it buzzed around me when I meditated at Buddhist Zen sittings, we found it high in the Himalayas, it was at the Ka’aba when I performed the Umrah, and it has always risen from the beats of drum circles. It is the access of Universal power of harmony and creation…and it is magical.

Goodbyes and Beyond

During our travels in East and Central Africa, the locals have been disappointed with the lack of rain this year, but that night in the Kalahari it just poured. It rained so hard for the entire night and I woke up so concerned about how the KhoiSan were managing in that heavy downpour. The crisp and damp morning couldn’t have come quickly enough, and we were all eager to go to the village and see how the community had survived the night.

They were all centered around a fire and while the ground and some of their skins were damp, the inside of the huts was dry. They seemed happy and said that they had prayed for this rain. That was what the trance dance the night before was in service to and the ancestors had answered their call. Kgamxoo Tixhao shared that he had followed Kgao Qam into deep trance to bring him back and that the ancestors weren’t sure if they’d let him go back to Earth. They had gone deep into the mountains and had an experience that they seemed to still be processing and recovering from. It was time for us to say goodbye to the group of amazing people. We did a few last games together and took a few pictures. I could tell the kids were sad to leave just as everyone was getting closer to each other.

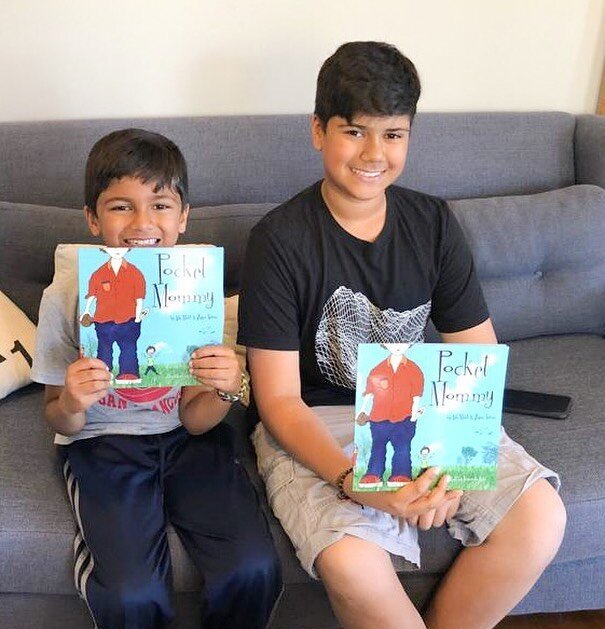

Untangling the “human knot” :)

We drove back to Xai Xai which is where most of the community lives when they are not in the Bush. The government of Botswana has given many of the KhoiSan free housing which Kavaa explained, feels very confining to some. In fact, some of the KhoiSan found toilets so foreign and unnecessary, that they use them for storing food! The village is very basic. It has a government funded school that some of the kids attend, one police officer/office, and a community center with an office for the leadership elected from the entire region.

As with most colonized indigenous peoples being forced into Westernization, alcoholism plagues the community. They are trapped between two cultures and are not set up for success in either one. They cannot hunt, so they cannot live fully in the ways that the ancestors did, and they have no means of reliable income in the Western world.

The government gave cows to the KhoiSan, likely in hopes that they would become herders, but that is not their way, and never was. They slaughtered the cows in turn as a community and feasted for a few months until they were gone. The irony of their situation is that the government will pay them a nominal few dollars to collect trash and recycle bottles, after which many will buy alcohol and litter the bottles, only to collect them for beer money the next day. It was a wake up call from the magic of the last three days and one which our family is prepared to answer.

We were, in a sense, family guinea pigs for what a model of responsible, compassionate tourism could look like with these special people and we can testify that it works. The model allowed the KhoiSan to be themselves, to teach the young kids their ways, and allowed some money to flow into the community. We were told that our visit, made them feel like they their culture was valued…and we all know, what is valued will be preserved. We have signed on to work with Rob’s team to support a soon-to-be-created foundation. My company, Venture Leadership Consultants, has taken them on as pro bono clients and are supporting their formation and fundraising efforts to create a conservation area where the KhoiSan can hunt and live in their traditional ways, to be supported by specialized responsible anthropological tourism.

We thank you for joining us on this part of our journey and for your witnessing of these beautiful people. If you would like to get involved with Rob’s Foundation, please connect with Golden Africa Safaris and they will compile a list of “friends of the Foundation” to be updated as the foundation officially forms in early 2020. If you are interested in visiting these special people, please contact, Phil at On Safari In Ltd and consider this special promotion to visit the KhoiSan in 2020.

An example of the “permanent” housing of the KhoiSan found in Xai Xai within a communal plot (see picture below).

—-

Excerpt from Kenza’s Journal (Age 9):

In Botswana there is a village called Xai Xai. If you go about a half hour away from the main more modern village (but still not a city) area you will reach a camp that me and my family stayed for three nights. Now, if you walk just past our dining tent, you will see a small path through the bush. After about five minutes of following the path, you will reach a tribe of about 26 people. And if you wake up every morning, have breakfast, and let that tribe take you into the bush (area with not many trees and sandy paths between bushes) then you would have done the same thing as me!

The first day we got to meet all the people in the tribe. My mom had a sweet and spicy mango chutney for the eldest woman. Right after she gave it to the woman she turned around to listen to our guide, Rob, telling us more about the culture and the people. Ten minutes later, my mom turned around only to see people drinking the more than half done chutney out of the jar (which was not really supposed to happen) then making disgusted faces (men coughing and spitting trying to get the taste out). Let’s just say it was not a great first impression.

That night Rob told us about the three different states of trance that the Bushmen go into for sort of a healing process. The first state is where the men feel attracted to the fire and get a little disbalanenced. The next is more of the healing process where the man in trance touches your head, shoulders, or chest, and gives blessings or energy. But most of the time they don’t go into the third trance (just by saying that, you probably know I never saw the third state of trance but I did see the first and second), but if they would, what would happen is that the soul of the man would completely leave him. When that happens the other men and women gather around the person and trance and feel his sort of “chi-point” (right behind the belly button) to see if they can get his soul back

We saw the first and second states of trance twice and both times the man put his hands on my shoulders. When they do that, their hands are trembling and you feel a source of power run through you, even though his actual hands are a bit cold and clammy. It was definitely a unique experience.

The next day I did not go to the first Bush Walk because it was a late night the night before when we saw the two men go into trance. I did go on the evening session, though, back at the village. The time the kids were all warming up to us. I drew in the sand with the girls while Zayan and Kaysan played a game with the boys where you have to bounce a stick as far as you can. That night the San people did not do a trance dance so we went to sleep early.

The next morning, I went on the morning Bush Walk deep into the bush to eat berries and try fruits and I got to have some more fun with my friends. In the afternoon, we skipped tea time because there was news from the village that some of the men were going out to hunt porcupine because they had found some tracks. So off we went. When we got there the men were already crawling into the porcupine burrow holes to see if they could find it. If they found a point where the tunnel was in the burrow, they started digging. Two hours later, they found a dead end to all the work and went home empty-handed. That night was our last night and the trance dance was on again. I was awake for a while but I just could not keep my eyes open, so I went back to camp with Zayan who was also falling asleep. I woke up in the middle of the night only to a rainpour and the light of my mom’s phone taking a video!

The next morning, Rob told us that long after we went to bed, the two older men did go into a third state of trance (too bad I didn’t get to see it). Like always we went to the village, but this time to play a few games and say goodbye.

Excerpt from Zayan’s Journal (Age 12):

The KhoiSan Bushmen also commonly referred to as the San people are a part of one of the oldest cultures in the world, that is now unfortunately dying due to Westernization. Therefore, I am all the more grateful that I had the honor of spending time with one of the last remaining San communities.

Our journey began as we boarded the Cessna plane for a long two-hour flight to a remote village, called Xai Xai (pronounced with clicks). Right away, I noticed how remote we really were. According to our guide, Rob, there is one dirt road leading to Xai Xai and that we were over a 12-hour car ride from any speck of civilization; but we did not stop there. We drove for what seemed like another hour, the last 15 minutes of which was a road completely through the Bush/trees, to arrive at our camp for the next three days. After lunch and a long conversation with our other guide, Kavaa (who was a Hereo man that had grown up with the San people ever since he was a little kid), we went to go meet the KhoiSan for the first time.

About a five-minute walk we got to a settlement with about four stick/grass hut structures that they all shared. We were greeted with a very warm welcome, but after that, everything fell into silence. To break the ice, my parents showed them pictures of our travels while I just took pictures of and for them with my Polaroid. Just as things started to warm up between us all, the sun started to go down and we had to leave. We went back to camp and had an excellent dinner before I got to witness something spectacular.

A trance dance is not something many outsiders have seen, so I consider us very lucky. Right after dinner, we heard the clapping and the singing of the KhoiSan, because of their proximity to the camp. Rob told us that we were going to walk over to their camp and watch a trance dance and he explained how they get into trances, or altered states to channel ancestral communication, wisdom, and healing.

When we got there, my first impression was that it was like the annual pow-wow my mom takes us to back home. A “pow-wow” is a native American gathering that now also serves as a dance competition and I was reminded of it because stomping is an integral part of the dances in both cultures.

After about an hour of singing and clapping, I noticed one of the men named Kgao Qam suddenly look like he had just been hit with two bottles of whiskey. Rob explained that he was now in a trance and that all the spiritual energy was now coming through him. Kgao Qam went around the circle healing people by putting his hands on people’s heads, shoulders, or chest, and chanting blessings. I too was healed and I felt some energy coursing through his hands. Thirty minutes later, we went back to the tent and I went to sleep, so excited by our first day in the Bush.

The highlights of the trip were by far the “Bush walks.” Everyday after breakfast, we embarked on a three to four-hour walk, learning what we could from the San people. One of my favorite lessons they taught the kids was how to track and dig-out burrows. When someone found a scorpion burrow, a young man sat on the top of the hole and started digging it up with a stick. Twenty minutes later, he grabbed the deadly bug by the head and passed it around like it was a doll! To clean off the dust from the scorpion’s body so we could see that it had four eyes, Kavaa even out it in his mouth! When they were done looking at the animal, they dug a new burrow (though not as intricate), and put it back inside, like it never happened in the first place.

I feel privileged knowing that I experienced this beautiful dying culture and I am happy that people like Rob make an effort with the government and limited tourism, to keep this culture alive.